I was watching Monday Night Football with my father in Fairbanks, Alaska, on Nov. 18, 1985, when I experienced my first NFL-induced trauma during a game between the New York Giants and Washington Redskins.

I was paying attention as well as any 7-year-old could — running circles around the living room essentially — I remember being frozen in place by my father jumping out of his chair and yelling at the TV screen in some mix of shock, despair and disgust.

I remember him telling me not to look at the TV. I remember my father’s girlfriend coming into the room and putting her hand over her mouth when she saw what just happened to Washington quarterback Joe Theismann’s leg — essentially snapped in half by Lawrence Taylor. It’s an injury so grotesque that I have never actually brought myself to watch it all these years later. I don’t feel the need to because I remember my father’s face.

It was the first time my memory was shocked into place by an NFL game. But it was far from being the last.

It happened again on Jan. 2 as all of us watched Damar Hamlin, a 24-year-old safety for the Buffalo Bills, fight for his life on a football field after making what looked like a pretty standard tackle against the Cincinnati Bengals. As I watched the hours of ensuing coverage on ESPN, my mind jumped to that day, almost 40 years ago, with my father. I thought about all the parents watching the Bills-Bengals game with their kids and trying to explain what just happened. To synthesize the trauma they’ve just witnessed. Like my father had to do with me almost 40 years ago.

We’re fortunate that, in a new era of compassion and understanding of mental health, the game was mercifully called off after Hamlin’s injury. There was no such thinking in past eras.

But it made me wonder — why do I keep watching the NFL if I know it’s going to keep doing this to me? Why do I keep watching if I know, eventually, I’m going to see something that traumatizes me? And what does that history of trauma look like, for my generation and the ones before and after me?

The Sitcom Theory

Peter Joneleit / AP Photo

I came up with a theory about NFL fandom a few years ago — I call it The Sitcom Theory — and it kind of explains how we end up in these situations time and time again in which we’re traumatized by what we see happen on the field.

It goes something like this: We don’t look at the players as real people. They’re essentially characters in a television series — which is any given NFL season — and the drama that unfolds is treated more like one of our favorite TV shows than anything else. And part of that is a testament to how popular the NFL has become and, therefore, how uber-famous the players are.

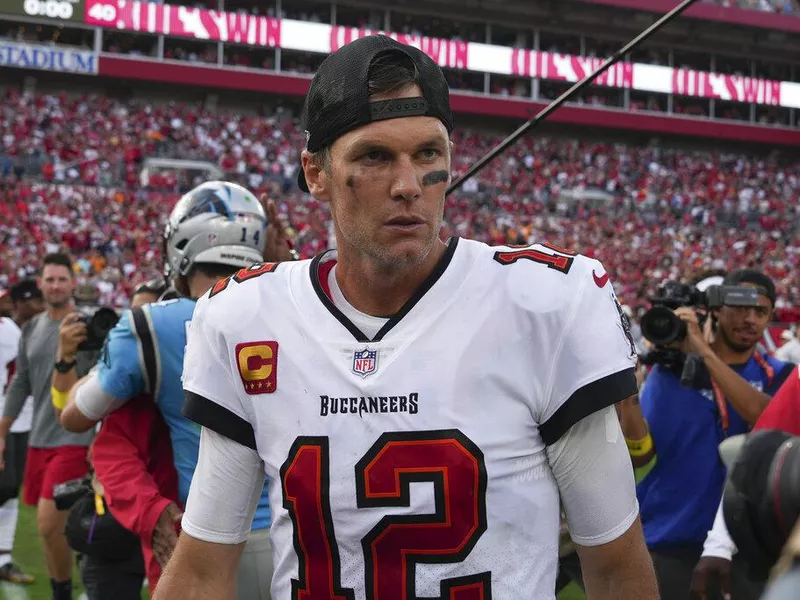

Let’s face it — you have about as much of a chance of meeting Tom Brady as you do of meeting a character from “House of the Dragon” or “Succession” because, in our reality, they only exist on our phones and on our televisions.

It’s only when something happens like what occurred with Hamlin when we see the real-world implications of what we normally view as entertainment. We are snapped back into reality despite our knowledge of the inherent violence of the sport. And that doesn’t happen very often.

The Murderers: O.J. Simpson, Rae Carruth, Aaron Hernandez

Reed Saxon / AP Photo

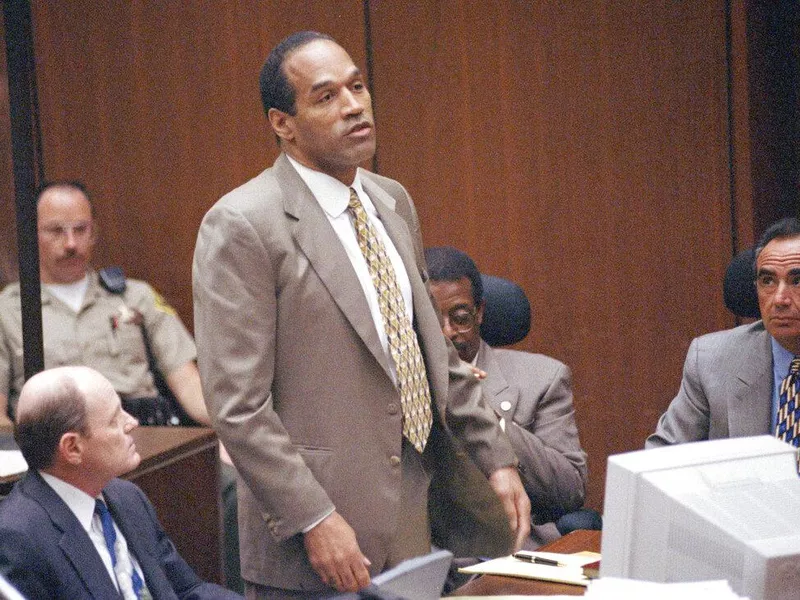

While these incidents didn’t occur on the field, they have involved the NFL and proved to be just as traumatic for fans over the years and bear mentioning — a string of players-turned-murderers who became as infamous as they once were popular.

Hall of Fame running back O.J. Simpson was acquitted in criminal court but found liable in a civil trial for the murders of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman in 1994 — two of the most famous murders in American history.

Charlotte Panthers wide receiver Rae Carruth orchestrated the murder-for-hire plot of his pregnant girlfriend, Cherica Adams, who was shot and killed outside of Carruth’s home by his associates in November 1999. Carruth went on the run and was eventually caught, tried and convicted and sentenced to 18 to 24 years in prison. Carruth and Adams’ son, Chancellor, lived but suffered severe brain damage. Carruth was released in 2018 after 18 years in prison.

In 2013, New England Patriots tight end was convicted of the murder of Odin Lloyd, the boyfriend of his fiance’s sister and sentenced to life in prison. After being acquitted of two more murders in 2017, Hernandez committed suicide in his prison cell.

So, Why Do I Keep Watching the NFL?

Joshua A. Bickel / AP Photo

I’ve often wondered if my sports-watching habits are a healthy thing, in general, especially at its most egregious levels during football season when I’m spending huge chunks of my weekends watching college games on Saturday and NFL games on Sunday.

That said, none of what I watch in any other context brings with it the baggage that watching the NFL does. I look back at a lifetime of traumatic football-viewing experiences and wonder what the draw continues to be. Some of it is FOMO — I want to be in on the discourse with my friends and family and the general public because I know they’re watching.

Part of it is my upbringing. My father coached high school football and wrestling. I played high school football and college football. I’ve spent 20 years since I graduated from college covering the sport almost nonstop.

The truth is I have some dependency issues when it comes to the NFL — like a blanket you can’t let go of when you’re a kid. And I don’t know how to break that cycle.

Let’s be honest, do I even want to?